Early spoiler for everyone – when Farinelli (real name: Carlo Broschi) thanked God for having a friend like Benedict (his employer’s paraplegic son), the young boy replied “God has nothing to do with it”. Even young folks like him are aware of the pain and suffering that performers like Farinelli go through in the quest of preserving their beautiful voices.

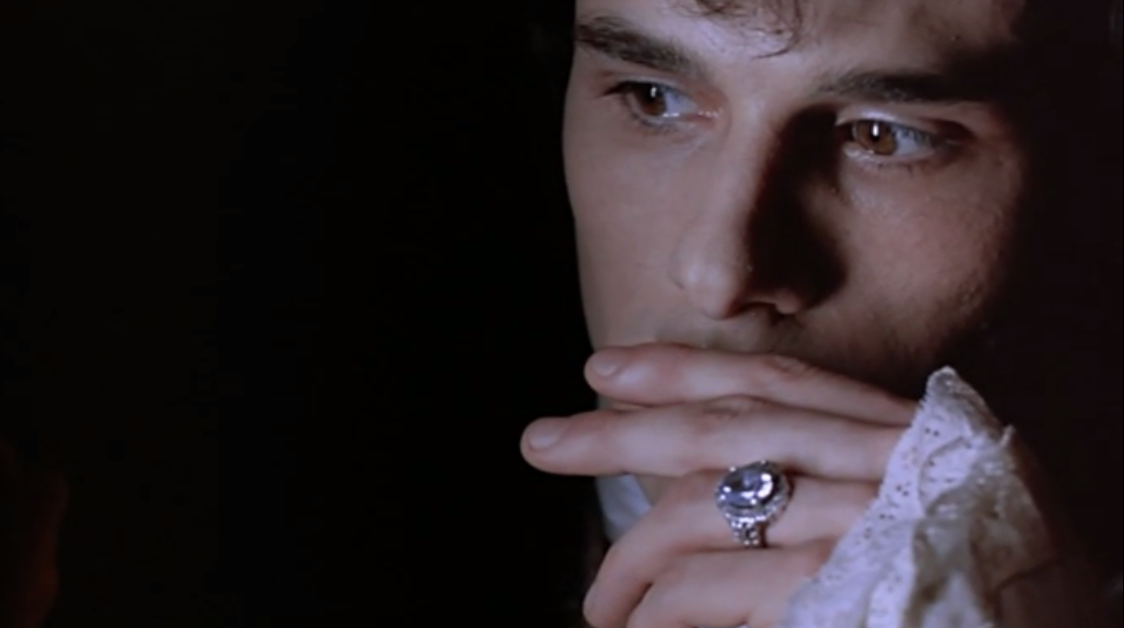

Farinelli earned international acclaim including an Academy Award nomination and a Golden Globe nomination for Best Foreign Language Film (for Belgium in 1994) for presenting an equal balance of glamour and barbarity that comes with the preservation of art. Barbarity because in order for some young boys to retain their angelic singing voices, they had to be castrated hence them getting called “castratos”. Historians may not like the extent of artistic license (or dramatic license if you may) that the director and writer took to present this story. But knowing that the last castrato had been long dead, it is impossible to get an actor to play the role of a castrato. So I understand if they end up getting someone (Stefano Dionisi) that looked entirely different from how a castrato is described to be. Now this ended up with a story that focused on the pain – both physiological and psychological that Carlo Maria Broschi had to endure in his quest for the ultimate art.

Background

Long before opera composers discovered that their male performers can use the full voice for the heroic roles (and long before women were officially allowed to perform in theater), young choir boys aged between 10 and 12 years old were forcibly castrated in an effort by their parents and respective choir masters to avoid the testosterone from enlarging their voices. It’s puberty that they are going against with. It was a rude awakening that Carlo found one day when one of the castrated choir boys leaped to his death – a suicide. It almost made him stop singing.

Fast-forward to years later and he’s one of the castrato draws in theater during the early 1700’s, the Golden Age of the castratos. Long before the “horror stories” involving prima donnas like Nellie Melba and Maria Callas, castratos like Farinelli demanded like divas. Long before rock stars became notorious for “groupies”, Farinelli was often seen backstage in bed with a female fan (because lack of testicles does not mean lack of sex drive). It’s sex, drugs (through opium) and music in the 1700’s. If ever there is some loyalty seen in him, it’s his loyalty to his composer brother, Riccardo, so much that he had the gall to turn down one of the top-sellers in opera, German baroque composer George Frideric Handel.

Extent of Artistic License

Most of the sidelights and dramatic highlights found here were already circulating in some documentaries. Perhaps the fact that these stories were given a face and a name to associate them with would proliferate some additional interest. But I do not recommend watching this film for historical purposes. There are books and documentaries online for you to browse on apart from Wikipedia.

It is true though that among the prominent castratos of that era, Farinelli is the only superstar that Handel could not hire for his operas. He had several castratos on the payroll but Farinelli was never included in that list. As for the movie presenting Handel as the villain, it’s only a reflection of the stiff competition between English opera companies at that time. There was even a scene in the movie where Handel is mobbed by some musicians claiming that they have yet to be paid for their work. Handel can’t pay them yet (allegedly) because Farinelli is killing the competition in terms of ticket sales. So no profit. And this was years after Farinelli turned him down to stick to his brother, Riccardo.

That’s the kind of charisma castratos like Farinelli have over their audience. He knew he can get by on his own. Harsh as it may sound, he doesn’t need Riccardo. It’s Riccardo who needs him so much that he even concocted a lie to justify his brother’s castration. He doesn’t need Handel either (maybe, a hypothesis on my part since Handel’s operas outlived even Handel himself). You know how some opera fans go for the star, not for the composer. This must have been why Farinelli enjoyed the chase he started with the latter.

Artistry Sought

Farinelli is portrayed here as the one after the artistry in his craft, not the money although he enjoyed the luxurious life. Every time he would talk to his brother about his compositions, he would criticize it as scores that are too reliant on trills, not the emotion that the song is trying to convey (Here’s a sample clip of Joyce DiDonato teaching a student how to trill her voice)

If Farinelli is used as a plot device to critique certain arias that rely too much on trills (or as they say in Filipino “pagkukulot”), then they succeeded in stressing out a point. Apply that analogy to contemporary pop music and you’d realize how some singers are more concerned about hitting the high notes and showing off with some vocal acrobatics than expressing the emotions that a song is trying to convey.

As an artist, Farinelli ends up getting into verbal arguments because of the way some audience members viewed him too. It’s an attitude bordering on being a prick. But when your “fans” praise your singing ability in your presence and mock your lack of testicles behind you, you need to put them in their place – behind you because you clearly ahead of them. In an industry where artists are objectified because they are often viewed as “freaks” (the term “castrato” is Riccardo’s derogatory term for his brother), Farinelli refuses to be treated as a freak but as a person.

Farinelli paid a high price for the artistry he sought after so much that once he found a nice retirement package, he grabbed it and left the opera life behind. The story is told in flashback with Farinelli already in Madrid, enjoying his retirement.

Influence

I don’t know what to say the moment I read on Norman Lebrecht’s website that some sopranos are losing their jobs to the countertenors. The purists still refuse to compare castratos to sopranos and mezzos despite having superstar Cecilia Bartoli headline concerts that features covers of castrato originals. But after some baroque opera scores like Artaserse (an opera performed with an all-male cast despite the presence of female characters) got restored, the demand for countertenors became evident.

There are still opera companies that hire mezzos to fill in roles originally occupied by castratos with mixed results. But now that some male performers have found ways to sing castrato arias without having to be castrated themselves, no need to feel awkward about putting mezzos in castrato roles. It’s like taking opera back to its roots with less pain this time around. If some men now can manage to sing like Farinelli without having to go under the knife, then a baroque resurgence might just occur.

The film “Farinelli” does not totally romanticize the baroque period in the point of view of the titular character. But since he cannot put his balls back into his nut sack, he just went on to become the biggest superstar of his era. It almost bordered on “You don’t know what I went through to get to where I am today” but at least he hasn’t forgotten hsi artistry. It may have produced some “divas” in the industry due to influence from icons like him but you can tell there is a dedication to the artistry, not commercialism, of the craft.

The film focused on the artistry and its effects on its stakeholders from the composers Riccardo, Porpora and Handel, to their prized muse. Perhaps my own complaint is that if one is not very familiar with opera, they would think that Farinelli’s performances presented here are just theatrically colorful concerts, not excerpts from productions with all the pomp and pageantry. Also it deviated a lot from history which is why I don’t recommend this as historical reference in case you need to research about the origins of opera. It will only give you an idea where to start so don’t take the circumstances presented here at face value.

Let me leave you with the lyrics of the aria that fitted Farinelli best in this film

| Original Lyrics | English Translation |

| Lascia ch’io pianga mia cruda sorte E che sospiri la liberta [2x] | Let me weep over my cruel fate And sigh for my lost freedom [2x] |

| E che sospiri E che sospiri la liberta | And sigh And sigh for my lost freedom |

| Lascia ch’io pianga mia cruda sorte E che sospiri la liberta | Let me weep over my cruel fate And sigh for my lost freedom |

| Il duolo infranga queste ritorte De miei martiri sol per pieta De miei martiri sol per pieta | May the pain shatter the chains Of my torments just out of mercy Of my torments just out of mercy |

| Lascia ch’io pianga mia cruda sorte E che sospiri la liberta | Let me weep over my cruel fate And sigh for my lost freedom |

For more updates regarding musicals and opera and everything in between, like our page, MusicalsOnline.com. For some positive reinforcement and inquiries if ever you need content providers for your website, like my Facebook page too, Purple Thunder Solutions. Thanks for reading.